I recently had the pleasure of joining James Beard nominated chef Ryan Roadhouse-san in his kitchen at Nodoguro. We discussed rice as well as his plans and plate for Feast Portland.

For those who’ve not yet had the pleasure of dining with Ryan Roadhouse, Nodoguro is an intimate 12-seat Japanese restaurant. The menu is pre-fixe, with tickets purchased online, in advance. One might call Nodoguro a “pop-up”, but I’m hesitant to use that label, as it is well established with a permanent home and consistent schedule.

Diners are seated around a large L-shaped bar, shared by Ryan and crew, as they plate and serve each dish. The experience is intimate, like being in the chef’s home kitchen. If you hail from Osaka, you may describe his approach as kappo cuisine; or if from Kyoto, kaiseki. Ryan refers to it as “sousaku”, literally “not sushi”— though he does offer a weekly “Hardcore Sushi Night” on Sundays.

What’s interesting is that the menu, often 9 courses, changes monthly based on customer-suggested themes; themes like “Twin Peaks”—of the Lynchian variety—or “Nodo in Wonderland”, taking inspiration from Alice in Wonderland. And all complete with elaborate, thematic decor. Even more interesting is that Ryan leaves the decision of the chosen theme to his wife and partner in Nodoguro, Elena Roadhouse. Something he says is difficult at times, but rewarding. “It pushes you to be more creative.”

Rice

In American culture we tend to see rice as a side dish or an accompaniment. In Japanese culture—and many Asian cultures—rice is the focus. It’s at the center of the meal. And historically, it was the meal.

“The language of a culture provides clues to important concepts and values. This is true in the Japanese culture. The primacy of rice as a diet staple is echoed in the Japanese language. “Gohan” is both the word for “cooked rice” as well as “meal.” … The use of gohan in Japanese is extended with prefixes to give usasagohan (breakfast), hirugohan (lunch), and bangohan (dinner). These multiple terms signal that it was almost impossible for most Japanese to think of a meal without rice.” — Linda S. Wojtan1

Types of Rice

At Nodoguro Ryan cooks two different types of rice. For the kappo dinners, it is a sasanishiki (pronounced: saw-saw-neesh-key) rice, grown in California. And for Hardcore Sushi nights they use koshihikari (pronounced: ko-she-he-kaw-dee), grown in Japan.

When asked why he uses two different types of rice, Ryan says it’s simply a matter of cost: “Sasanishiki is the highest quality you will find at most any Japanese restaurants here in town [Portland]. For our sushi nights, with each ingredient we are trying to do something totally different … Even as cost prohibitive as the sasanishiki rice is for most places, the Japanese rice is way more expensive. But for me—and because we’re only serving ten to twelve people—it’s totally worth it. As great as this rice is (holding the sasanishiki rice in hand), the koshihikari is mind-blowing for me.”

Koshihikari is widely considered by Japanese to be the best rice available. Koshihikari from the Niigata Prefecture—like the kind used at Nodoguro—is often the most expensive.

Quality and Moisture

“Koshihikari has significantly more ‘embedded moisture’”, says Ryan. Holding the sasanishiki rice up close for me to inspect, he shows me that it has “little fissures, cracks, and opaque spots.” When cooking the sasanishiki and koshihikari with the same amount of water, “the Koshihikari grains will puff up to big fat juicy rice.”, says Ryan, demonstrating that the koshihikari contains more “embedded moisture” to begin with. He explains that “one big difference between the Japanese- and California-grown rice has to do with the growing methods … with Californian rice they are growing with irrigation. Whereas in Japan, you have completely flooded rice paddies. That’s where the increased moisture comes in.”

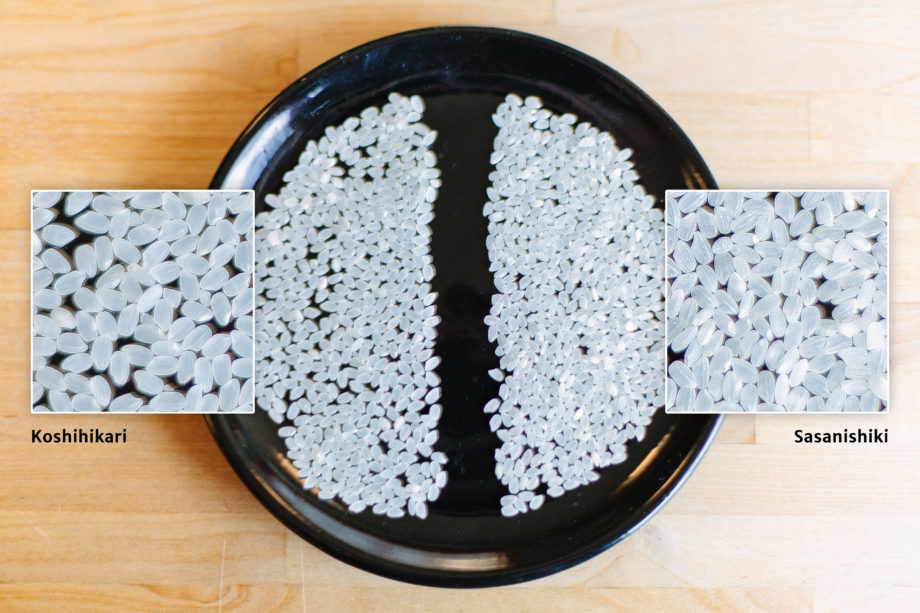

Koshihikari (left) and Sasanishiki (right) rice comparison; note the small cracks and opaque spots in the Sasanishiki

As rice ages it loses moisture. “Working with rice all year long, in the late fall you get what’s called the ‘new crop’ … the moisture content is much higher and it’s a lot easier to cook. It just requires a lot less fussing.” he says. “You get it, you wash it, you boil it. With new rice—a new crop—the necessity for [added] water goes way down. It’s already got a lot higher water content. As the rice ages, it gets dryer and dryer”, adds Ryan, and “cooking becomes more complicated. It may require an extended soak, a little bit more [cooking] water—or if you have pressure capability, increasing the pressure.”

Ryan goes on to say: “That being said, a lot of people say that for sushi the older rice is better. Because of the fact that you can control that moisture content. With sushi, you want to make sure that you have nice firm grains that can stand up to some handling.”

Qualities of Well-Cooked Rice

I ask Ryan what qualities we should look for in well-cooked rice: “With sushi rice—any rice really—you want that perfect moisture content. It’s firm and aromatic, but it doesn’t have any of the signals of being undercooked, or dry … sometimes [in bad rice] you get that mashed potato texture.” I echo his sentiments. Perfectly cooked rice straddles the line between firm and soft, retaining each individual grain. It’s just sticky enough to hold together, but not so much as it’s gummy.

Water

Ryan and I discussed the use of special filtered or spring waters for cooking rice. He said he had “used to worry about that”, but doesn’t give it much thought any more. We both agreed that the tap water in Portland is ideal because it is so soft. If you live in an area with hard water, you may consider using filtered water.

Massaging Rice

Many recipes call for “gently massaging” or “rubbing” the rice while washing. The idea being that this hastens the release of starch. Ryan says don’t do it. “You see a lot—and these are not home cooks, these are professional kitchens—you see a lot of people aggressively rinsing the rice. Rubbing it. Things like that. The Japanese rice that I use can probably stand up to some of that. But what happens when you are using a California—even a California high-grade rice—when you look through this rice (he rolls a few grains between his fingers), you can see a lot of little fissures and cracks. This is because this rice tends to be more dry and brittle. So what happens when you rub the rice (he rubs the rice gently between his hands), you get more and more cracks. More broken, smaller pieces of rice. Now when you look at your bowl of rice, instead of getting the big, plump grains of rice, that are fairly uniform, you end up with these little pieces of smashed and cracked rice.” So don’t rub your rice? “Yeah. I say don’t do it. Let the water do the work. Just guide it. Treat it really, really gently.”

Perfect Rice

The Japanese have a word: Kaizen. Literally, “Change-Good”. Or “change for the better”, which could be interpreted as “continual improvement”. The striving for perfection. No one exemplifies this pursuit better than the Japanese. And their dedication to growing and cooking the perfect rice is no exception.

As such, everyone has their own take on what constitutes the best way to cook rice. Maybe that’s in a donabe, or a modern rice cooker. Or perhaps it involves washing 5 times. Or maybe 7. After all, perfection is necessarily subjective.

How to Make Sushi Rice (shari)

What follows is my take, with advice from chef Ryan, on making high-quality sushi rice. You can break it down into 6 parts: Rice, Rinsing, Soaking, Drying, Cooking, and Seasoning

Rice

No amount of effort will make up for low-quality rice. Buy the best rice you can afford. There are many California-grown rices that are of very high quality. For koshihikari rice, the Tamaki Gold brand is excellent, as is Shirakiku koshihikari. For sasanishiki, the Nozomi brand is also very good.

Rinsing

Easy does it. Don’t manhandle the rice. Place the rice in a deep bowl and fill with cold water. Swirl the rice around to remove the starch and polishing remnants. Plenty of water aids in the rinsing. Rinse for about 15 seconds, then discard the water. Repeat one more time. It’s important to not let the rice soak in the starch-rich water. Now either transfer the rice to a strainer, as I prefer, or continue in the bowl.

If using a strainer, use one small enough to sit flush with the top of the bowl. Continue rinsing, discarding water as it fills the bowl. Rinse until the water is clear, dumping the bowl each time it fills. This takes anywhere from four to eight times. Ryan says “seven”. The water will never be crystal clear, but it shouldn’t be overly foggy.

Soaking

Soaking depends on the hydration level of the rice. New crop rice will contain the most moisture and requires little soaking. As rice ages it loses moisture and benefits from a longer soak. New crop rice is typically harvested in October, November and December, but many brands are harvested year round. Soak from 15 minutes to as long as an hour, for year-plus-old rice. A tip Ryan provides is to angle the bowl slightly and run a small stream of water. This causes any residual starch and polishing material to rise up and spill over as the rice is soaking. He also adds that with Japanese-grown koshihikari rice, there is “little to no soaking”, but with the California rice they will soak for 15 minutes to an hour.

Drying

After soaking comes drying. This is typically done in a strainer over a bowl, allowing the water to drip off and the rice to dry. I have yet to find someone who can explain why drying is important, but it’s widely considered a critical step. The quality difference of rice cooked with and without drying is obvious when compared side by side.

Rice drying comparison: 5 min. (left), mostly transparent; 10 min. (middle), half transparent, turning white; 15 min. (right) brilliant white, shiny

15 to 30 minutes is a typical drying time. You are looking for the appearance to change from semi-transparent to brilliant opaque white (see illustration). When there are no traces of transparent spots, the rice is dry. Ryan says: “Whenever we make a batch of rice for a dinner here [Nodoguro], we dry the rice for at least 30 minutes.”

Cooking

Great rice can be cooked in a simple pot, but a rice cooker is easier and produces perfect rice with little oversight or effort. Rice cookers range from simple electric rice cookers, to advanced computerized models with induction and pressure. I’m a staunch supporter of Zojirushi brand rice cookers. Chef Ryan uses a no-frills, commercial rice cooker.

A donabe, or literally “earthenware pot”, is a traditional vessel for cooking rice. They are typically glazed on the inside and unglazed and porous on the outside. One benefit of rice cooked in a donabe—or other pot— is the crispy layer that forms on the bottom. The japanese call this okoge. Perfectly brown and crunchy okoge is a simple pleasure not to be missed. The high-end line by Zojirushi actually has the ability to include a scorch cycle to produce okoge.

Rice-to-Water Ratio: Donabe, Pots and Simple Rice Cookers

Rudimentary recipes often call for a rice to water ratio of 1:2 by volume, meaning 1 cup of rice to 2 cups of water. This is often too much water, especially if soaking. Ryan says they use a starting ratio of 1:1 by weight (note this is not volume), with slightly less water than rice. For example, 500 g of dry rice to 490 g of water.

Rice-to-Water Ratio: Advanced Rice Cookers

Rice cookers typically have a water fill line. Some, like mine, have different fill lines depending on the type of rice and desired softness (e.g. sushi, regular, soft, hard, porridge, etc.). Less sophisticated rice cookers are not accounting for rice that has been properly soaked, and as such instruct you to use more water than necessary. In my rice cooker, properly soaked rice and water 1-2 mm below the fill line produces the best result.

After cooking is complete, rice is transferred to a hangiri, a rice mixing tub made from cypress wood. The goal is to cool the rice down quickly, to around body temperature. This can, of course, be done in any large bowl or sheet pan. The advantage of the hangiri is that the wood partially absorbs the moisture and steam while cooling; where a non-porous bowl would simply sweat and pool water. The rice is spread thin and cooled with a paper fan.

Seasoning (shari-zu)

After cooling the rice is seasoned with a sweetened vinegar mixture called shari-zu. The amount of shari-zu used is highly subjective. Seasoning is applied while rice is in the hangiri. Shari-zu is drizzled over the rice paddle while making a horizontal slicing motion to evenly distribute across the rice. Rice is then “cut” gently with the paddle to mix in the seasoning.

When asked how he approaches shari-zu, Ryan says, “for some [shari-zu] recipes the sugar is profound … I’ve seen 4 parts vinegar to 3.5 parts sugar. That’s nearly the level of a syrup. For mine, I like the vinegar more at the forefront—for it to have some sourness to it.” Ryan also emphasizes the importance of salt, which he says is “something many people don’t use.”

Shari-zu is typically made with vinegar, sugar, sometimes mirin, and salt. There are two types of vinegar used in shari-zu: Komezu and Akazu

Komezu

Komezu is the rice vinegar most are familiar with. Most rice vinegar is made from rice and some other form of starch. Harder to find is rice vinegar made from only rice, called jun-komezu, which is considered superior in flavor. Ryan uses Mizkan Shiragiku brand.

Akazu

Akazu is often referred to as red vinegar due to it’s redish-brown color. Akazu is made from sake lees, the left overs from sake production. Akazu has a more pronounced flavor than komezu, with notes of caramel. Ryan uses Mizkan Yusen brand.

Nodoguro’s Shari-zu Recipe

Parts |

Percentage % |

Weight |

Ingredient |

| 2 parts | 100% | 200 g | rice vinegar (komezu 米酢) |

| 2 parts | 100% | 200 g | sake lees vinegar (akazu 赤酢) |

| 1.5 parts | 75% | 150 g | white sugar |

| 0.5 parts | 25% | 50 g | sea salt |

Tips for Great Rice:

- Buy good quality, short grain rice

- Store rice in an air-tight container, in vegetable drawer, in your refrigerator

- Be gentle with the rice when rinsing

- Try to gauge the age of the rice; either by the manufacturers labeling, or by it’s appearance

- Soak your rice according to age; soaking longer the older it is

- Dry your rice for 15 minutes after soaking, and before cooking

- Experiment with rice-to-water ratios; adjusting to your desired firmness

- Seek out akazu vinegar; it’s difficult to find, but worth the effort

- Try your rice plain; a simple bowl of rice can be a great pleasure

References:

1. Wojtan, Linda. “RICE: It’s More Than Just a Food.” November 1, 1993.

14 Comments

-

I love this post, Kyle. I really should make it back to Nodoguro and see Ryan. Thank you for the awesome breakdown ?

-

Author

Thank you, sir.

-

Inspired by this post I tracked down some Tamaki Gold decently priced (~$1.99/lb) at a local asian market and went for it. I’ve attempted sushi rice before but had never done the presoak and drying steps with a premium brand – what a difference! Was cool to see how brilliantly white it became after drying. Rice was excellent – next time I’ll use your ratios exactly (I tried Tamaki’s suggested 1 rice : 1.1 water and it was a touch too sticky for my taste). Thanks for the article!

-

Author

Excellent. Happy to hear you had positive results. Thanks for sharing.

-

-

-

So glad you included “try your rice plain,” as there is nothing better than a bowl of properly cooked rice, especially when it is New Crop. Sadly, rice in the US is often the Rodney Dangerfield of starches. It deserves far more respect…if not reverence.

As a side note on the okoge, one of the best we ever had was at a small restaurant in Kyoto. The owner, Hisao Nakahigashi, served everyone a small piece of the okoge paired with house-made shiso oil and Japanese sea salt toward the end of our multi-course meal. You broke off a piece of the okoge, dipped it lightly in the shiso oil, and then scattered a few flakes of salt on it. Absolutely sublime. And I would’ve given just about anything to take home his gohan no donabe. It was custom made by a Shigaraki potter friend of Hisao’s. The picture here – http://www.japanesefoodreport.com/2007/11/cooking-rice-in-a-donabe.html – is beautiful, but you should’ve seen it in person!

All the best… Mora

-

What a great post. My brother and I source fish and make sushi ourselves for parties and such. I always felt I made good sushi-rice that was workable, and had just the right tack. But I never knew about drying it. I’ll be trying that soon. Thanks.

-

Author

Thanks, Jason. I’m still learning too. Try to get some of that sake lees vinegar. It takes it to a whole new level.

-

-

This has got to be the most informative article on making rice that I’ve ever read! It answered so many questions I’ve had about cooking rice. I didn’t know about pre-soaking. So whenever I followed the directions for making sushi rice, it never came out fully cooked and so I thought the recipes were just a bunch of nonsense. Now I know they weren’t nonsense; they were just incomplete!

-

Author

I’m very happy to hear that, Tim. That certainly makes the effort worth while. To appreciate well-cooked rice is a rarity here in the states. Glad I’m not alone. Let me know how your next batch turns out. Try to figure out the date of harvest–many of these are embedded in the production code on back. Then use that to gauge how long you should soak; older being longer.

-

-

Thanks Kyle for this wonderful page on cooking rice! You address so many questions about nuance that I have had for many years. I will try to seek out a hangiri and some azuka. I had a quick question on drying and using a cooker with a built-in soak. We were just gifted a small zojirushi rice cooker (cooks beautifully) and wondered if there’s a way to dry after the automatic soaking cycle. Appreciate any tips on this and again, thanks for a brilliant and concise reference for one of life’s most important basics.

-

Author

Ian, I’m very happy to hear that. To Tel you the truth, I’m still not totally certain on pre- or post-soak drying. When I use the rice maker, I go through all the washing, then let it dry for 20m until bright white. Then I add it to the rice maker and let it do its thing. I have the same, and it does have a presoak. Roadhouse uses a rice maker, buts it’s very analog and starts boiling straight away. I’m still learning to use my donabe and fail in that process. Hope that’s helpful.

-

-

Fascinating reading! Studying your posts all afternoon. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and expertise. I’d not know so much about fish sauce, now I do. Ordered your winners; can’t wait to sample them. Fr. Dave

-

Author

Thank you, David. Happy to have you.

-